Now that we have access to compounded FIP treatment, one of the first questions I often hear is, “I’ve prescribed the medication — now what?”

Generally speaking, and especially at the beginning of treatment, the clinical response is the most important aspect to monitor. Poor clinical response may mean that the dosage needs to be adjusted, additional supportive care may be needed, or an alternative antiviral treatment (eg. Molnupiravir, Paxlovid) may be indicated. Cats presenting with FIP may also have other comorbid conditions which require specific supportive care, treatment and monitoring, such as IMHA, upper respiratory infections, etc. and it can be important to differentiate whether or not a cat may be responding to FIP treatment but require separate treatment for a comorbid condition.

Another key component of monitoring FIP treatment is ensuring that a cat is weighed regularly throughout treatment and adjusting the dose as appropriate for weight gain. I cannot emphasize this point enough — not increasing the dose to remain in line with weight gain appears to be one of the most common causes of FIP treatment failure.

Monitoring Timeline

48 hours – This can be a verbal checkin, or an in-clinic visit, but we are looking for signs of improvement within the first 2-5 days after beginning treatment.

Within this timeframe, you should see resolution of pyrexia, increased appetite, and activity level. This can also be an important time to evaluate supportive care needs, and address any difficulties with medicating the cat.

Note that some cats with pleural effusion may require drainage after starting treatment, until the medication has had time to take full effect. Until the pleural effusion is resolved, instruct owners to monitor respiratory rate and advise them when and how (eg. normal clinic hours vs. emergency hospital visits) to seek medical assistance.

In some cases, neurological or ocular symptoms may declare themselves early in treatment — this does not necessarily mean that the drugs are not working, but indicates that a dosage increase to the neurological/ocular dosages is warranted. Neurological and ocular FIP require higher dosages in order to allow sufficient amounts of the drug to penetrate the blood-brain and blood-eye barriers.

2 weeks – Depending on client finances and cat’s clinical response, this visit could be done as a verbal check-in, or as an in-clinic visit. At this stage, the cat should be significantly improved in appetite and activity, any effusions should be either resolved, or nearly so, and there should be definite improvement (if not resolution) of ocular and neurological symptoms. At this point it is important to obtain a current weight for the cat and verify whether the dose needs to be adjusted — many cats will have already begun to gain weight at this point in treatment.

6 weeks – At six weeks, most cats will seem clinically well — if they are not this is likely a warning sign. A CBC and chemistry panel is often run at this point. The bloodwork has often largely normalized at this point. (see below) Again, it is important to weigh the cat and adjust the dose for weight gain as necessary.

12 weeks – Before stopping treatment, the cat should be examined and the CBC and chemistry panels repeated to evaluate whether a cat is ready to end treatment. Most importantly, the cat should seem clinically well, with appetite and activity levels normalized, and all symptoms resolved.

That said, some cats may have mild persistent lymphadenomegaly or scant effusion which is not associated with causing a relapse. Cats diagnosed with neurological FIP, particularly those with spinal involvement and urinary and/or fecal incontinence may also have some residual permanent changes due to persistent hydrocephalus and syringomyelia.

Biochemistry and haematological values should also ideally be normal. Some cats may have persistent hyperglobulinaemia, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, and this is not associated with relapse.

Hematological and serum chemistry changes

There are a few trends seen in hematological and chemistry values during treatment for FIP. A few of them often take clinicians by surprise as it may appear that a patient’s values are worse, despite their much improved clinical appearance. Let’s examine a few of the most significant trends.

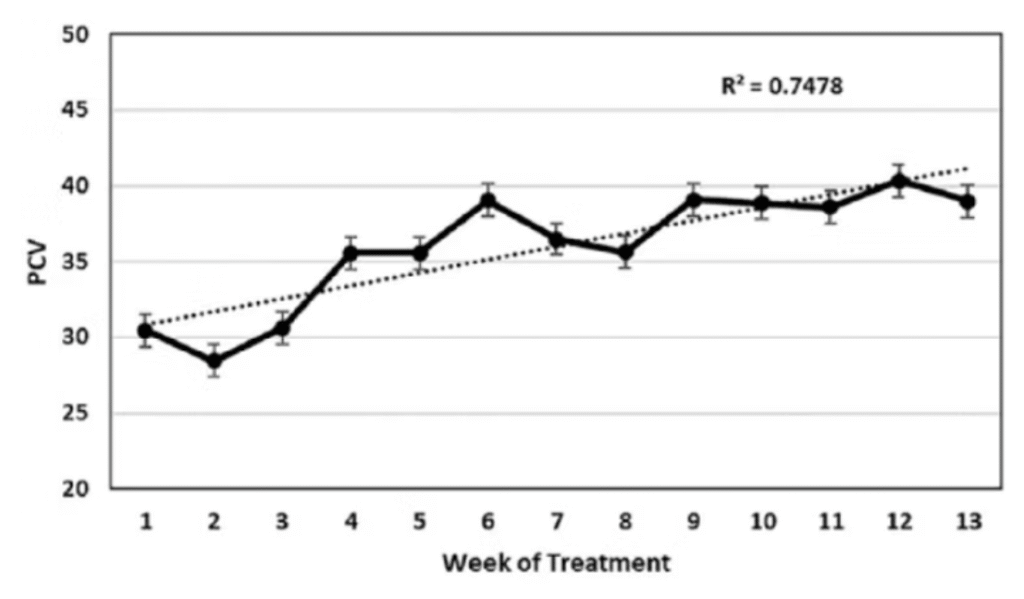

• PCVs will gradually return to normal levels about 6–8 weeks into treatment, but there may be a transient dip early on, around the week 2 mark.

• Initial leukocytosis (usually neutrophilic) typically resolves within the first 2 weeks of treatment. Lymphopenia often resolves after a week of treatment, with fluctuating lymphocyte levels throughout treatment. Some cats experience lymphocytosis, which may persist for several months after treatment ends.

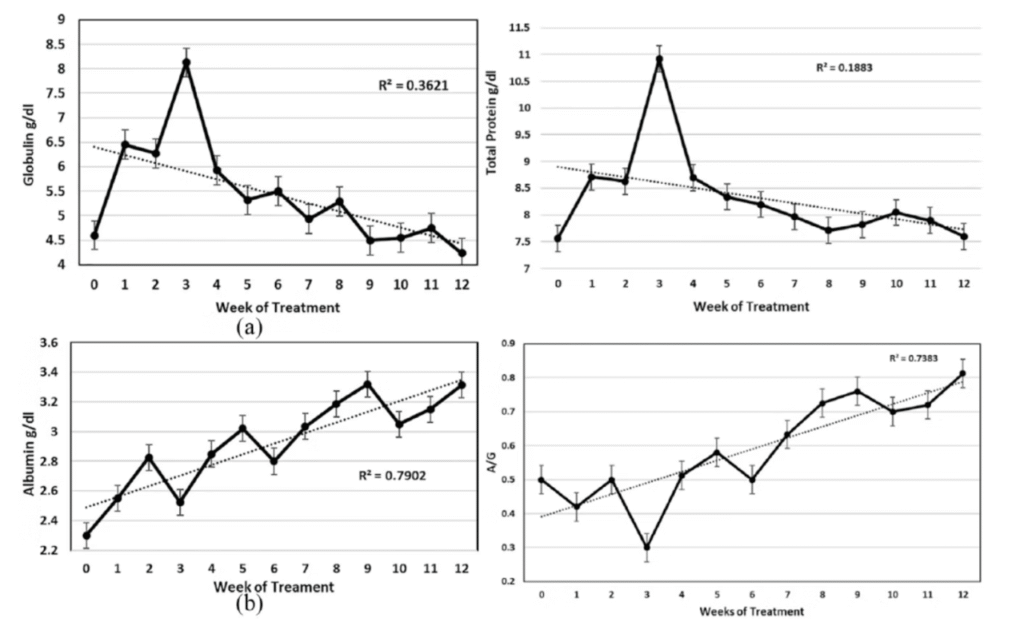

• Despite clinical improvement, globulin levels may rise and fall during the first few weeks of treatment, with a dramatic rise 2-3 weeks into treatment, roughly corresponding with the timeframe when abdominal effusions are resolving. At this point, the amount of globulins may be higher than even at initial diagnosis. This high value may seem startling, but if the patient is doing well clinically is not cause for alarm.

• No significant changes are typically seen in ALT, AST, ALP, lipase, amylase, BUN or creatinine levels during treatment. A few cats (particularly older cats, or cats with already compromised kidneys) may see rising BUN, creatinine and SDMA values associated with GS-441524 treatment.

Figures excerpted from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6435921/

References:

Taylor S, Tasker S, Gunn-Moore D, Barker E, Sorrell S. An update on treatment of FIP using antiviral drugs in 2024: growing experience but more to learn. International Cat Care. November 2024. Accessed June 5, 2025. https://icatcare.org/resources/fip-vet-update-november-2024.pdf

Pedersen NC, Perron M, Bannasch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog GS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21(4):271-281. doi:10.1177/1098612X19825701